In the past, when I came back to Beirut, I would ask my friends what I could bring them from the States. “Nothing” was the cheerful reply, “we have everything here”. I’d just bring friends a box of maple cream cookies or salt water taffy, little treats from America, and consider the job done.

This time it was different. Along with the maple creams and taffy went their requests, among which were: Tylenol, aspirin, Salonpas, vitamins, make-up, brown sugar, Crest toothpaste, walking shoes, flea collars, fleece blankets, flashlights, prunes, and vegetable seeds. One friend likes to make her mother chocolate chip cookies so I brought six bags of those; another friend misses a licorice candy so that went into the bag. The children of another were missing Kraft macaroni so those, too, made it in. I also packed large jars of Nescafe which is very popular here for some reason and is now a luxury item and special treat. Land’s End had a sale on down vests so I ordered one for each friend and for myself, knowing how cold it gets with stone floors during the winter rains.

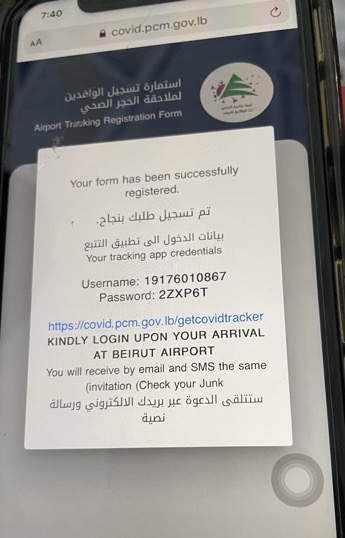

I did not neglect my own needs. Friends told me to bring all my own toiletries, so I did but I drew the line at shampoo. It’s too heavy and could spill. I didn’t even buy a plane ticket until I had three months of my medications in hand. I packed a three pound bag of vegetable wash and batteries for my flashlight and reading light. I also packed a canister of pepper spray for myself and the daughter of a friend whose 14th floor apartment with the spectacular view now requires hiking up and down stairs where anyone could be lurking. The lack of electricity means that building security gates are often open for hours at a time. This is true in the building I am staying in as well.

In packing clothes, I thought about how difficult it might be to find a functioning dry cleaner and even reliable electricity for an iron. I packed all knitwear. I thought about walking up seven flights of stairs to my AirBnB apartment, and walking down, and left my long raincoat at home lest I trip on its hem. I packed thermal underwear, a duvet, and a wool throw because the apartment doesn’t have heat except during business hours as the building is mostly office space. The landlord offered me a space heater with a gas canister but it looked like something that would blow up in my face and I asked him to take it away. As I write this I am keeping myself warm with three layers of clothing and a woolen wrap.

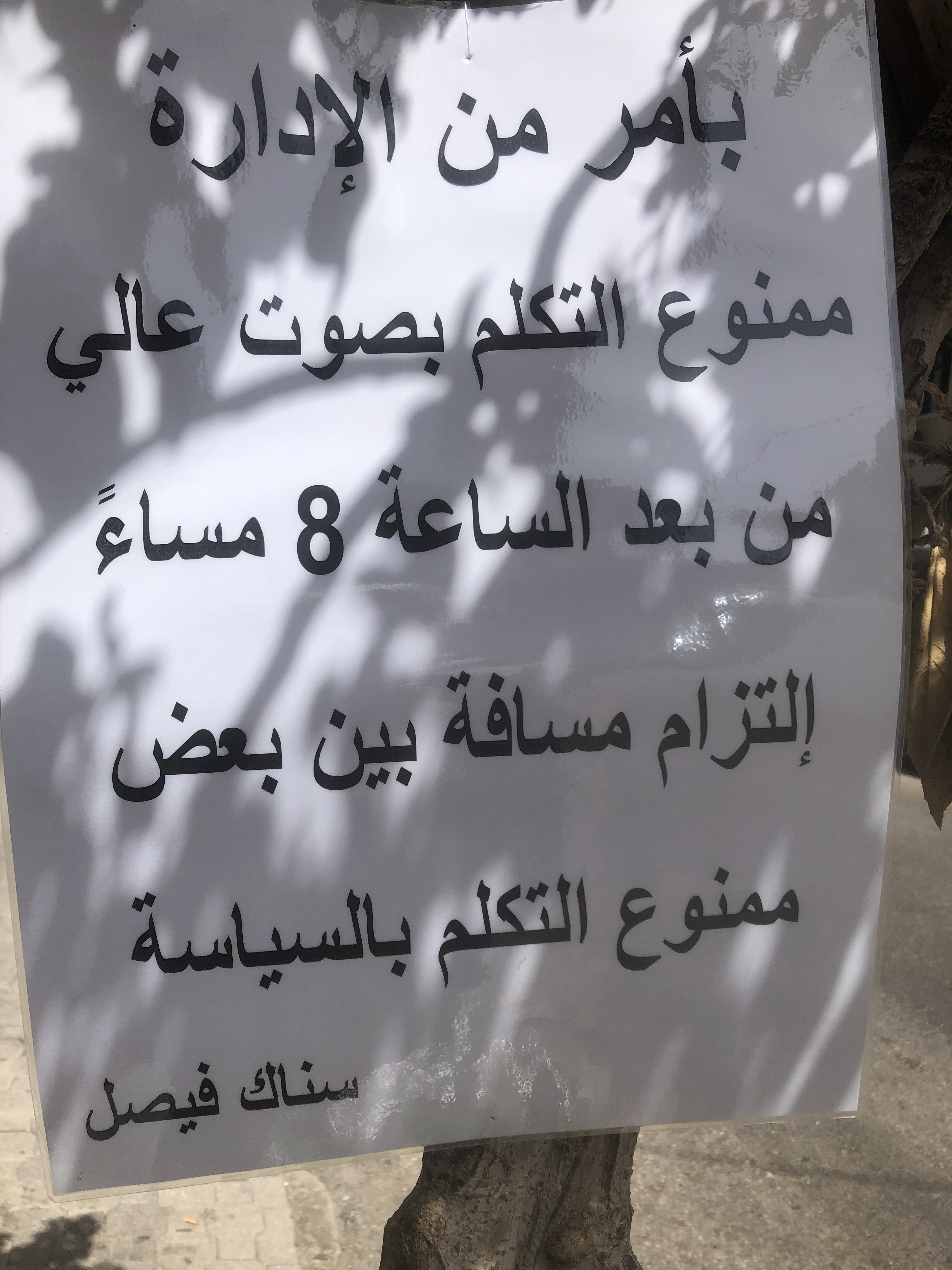

I am staying in a new apartment this year. The landlord of last year’s apartment doubled the rent in dollars. This reflects the increasingly two-tiered reality of Lebanon these days. Those who have the means to insulate themselves from the higher prices pay dearly for the three sources of utility power these days: government supplied electricity (if any), back-up generator electricity (about 10 hours a day) and battery supplied electricity to a few wall outlets. The most deluxe buildings have two generator contracts but even they don’t have 24/7 coverage. In my apartment, I can’t use the oven or microwave after 7 p.m. or on weekends. I don’t need to be reminded that this is a high class problem. Most of Lebanon is sitting in the cold and darkness. This is the coldest winter in forty years. It snowed in Beirut a few days before my arrival. A dentist friend had to close his clinic those days as it was too cold for his hands to work.

I am still getting my bearings in this land of scarcity. There are two supermarkets in my neighborhood, a Spinney’s and the more down-market co-op. Spinney’s didn’t have flour last week, nor butter. Its selection of goods is pared down. No more Asian products like tofu or European cheeses like Parmesan. I expect this reflects not only the high cost of imports but also the loss of the customer base — the cosmopolitan professionals who have left the country in droves. Walking down the supermarket aisles one sees that most of the manufactured goods come from Turkey these days. This has always been considered the inferior stuff. But it’s all inferior stuff in the supermarket these days: it is clear that the Lebanese agricultural sector is sending everything it can abroad, leaving the Lebanese with the bruised and misshapen remainders. There is one exception: a special refrigerated section at Spinney’s displaying exquisite baby vegetables and choice fruits. They even had lychee nuts last week from South Africa. It was almost an affront.

Watching people shop for food is truly painful. Their faces are etched with anxiety. For the first time I’ve seen couples shopping together as the purchase of food is now a major financial undertaking for the household. Before last June most basic foodstuffs were subsidized and were very cheap. Now the prices paid for food reflects the fact that Lebanon imports 80% of what it consumes and is paying for it with increasingly expensive dollars. Many shoppers use their cell phone calculators to keep within budget. They price-check before placing items in their baskets. While standing in the checkout line they lament prices together. There are always items to be re-shelved at the head of the checkout counter.

Just after I arrived, a friend came over for coffee and said it was nice to see me because mine was the one face she’d seen lately that was not taut with anxiety. Now I see why.

God knows what is going to happen to this country but story a friend told me does not bode well. An acquaintance of his, who is an army officer, told of a soldier in his unit who showed up late for muster. “You’re late!” he shouted at the soldier. The soldier replied, “You’re lucky I came at all”. Instead of disciplining the soldier for insubordination the officer responded, “You’re right”. That soldier’s pay used to have the purchasing power of $800/month in an economy with subsidized goods. Now his salary has the purchasing power of $55/month with nothing subsidized. This is the one public institution in Lebanon that most Lebanese respect and that many credit with holding the country together. What happens if it unravels?