I thought about not returning to Beirut this year. Apart from traveling in the middle of a global pandemic I’d be going to a country whose hospital system had been crippled by the port blast. Seeing my friends was going to be tough as the Lebanese government has always taken the pandemic seriously and is implementing strict lockdown measures. Any Arabic instruction that I take these days will be over the internet, but in Lebanon the internet is wobbly at best. Not to mention the electrical grid, which is near collapse and is only providing three hours of electricity a day from the government. But my main personal concern about being in Lebanon these days is personal security. With nearly half the population living in poverty now it’s only expected that crime is on the rise. My Lebanese friends are worried about crime, too.

But then I thought of how I’d miss people if I didn’t come back. And how it felt like a betrayal not to come back during this season of despair. And how, when I asked them what they needed I saw I could at least make their lives a little easier by bringing the requested toothpaste, deodorant, over the counter medications, vitamins, foodstuffs, and clothing. I filled an entire suitcase with these items. Because things are really that bad in Lebanon. The collapse of the currency to 12% of its former value has made the import of everyday items very difficult. My one proviso for coming back was that a friend scurry about Beirut and gather up a supply of my medications so my own health wouldn’t suffer.

Implementing my return was no easy matter. The Lebanese Consulate closed for three weeks around Christmas due to a Covid outbreak there after which they would only accept documents by mail. Not Fedex. Not courier service. Only USPS mail. The very service that the Former Guy did his very best to destroy and which was still delivering packages mailed in early December a month later. No way was I going to submit my passport to the vagaries of a sabotaged mail service, not to mention a consulate where the mail wasn’t even getting collected regularly. I was going to have to get a one-month visa at the airport and deal with an extension later.

And then there was the flight. I had read enough about air circulation on airplanes (I can’t believe I wrote a sentence like that) to know that one sits by the window or one doesn’t board the airplane. Qatar Airlines wouldn’t let me choose my seat in advance of booking as I was delaying my scheduled return. I just took a chance that a mid-week flight would be okay and it was. I was prepared to throw the ticket away otherwise.

All set, thought I. I just needed to notify the apartment hotel of my date of return. Alas, they informed me, they had just closed. All those good people thrown out of work with no government safety net to catch them. They now have to rely on a patchwork of help from family, friends, U.N. agencies, NGOs, and, of course, the sectarian political parties looking to buy their votes. I was going to miss them and my rundown apartment with the lovely view of the sea. I had anticipated this possibility last spring so I had looked around then. I settled on one in an adjacent neighborhood near the sea which had a view. I do love watching the sun set and the planes come in to land. So, I notified my Plan B apartment hotel and it was all set.

As the day of my departure approached, I had to submit to the caprices of PCR testing. The Lebanese government requires a negative result within 96 hours of the flight. In Beirut one gets one’s PCR test back within 24 hours but in New York last August it took almost two weeks for me to get a result. So, I spread the risk around and did two tests in New Hampshire – one came back too early to be useful – and a test in NYC. The NYC test came back with 48 hours to spare.

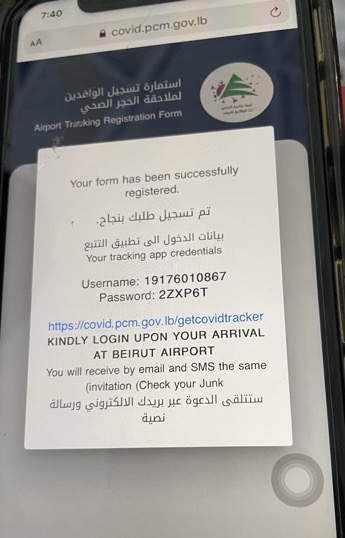

And finally, on the day of my departure there was the form to submit to the Ministry of Public Health showing one’s negative Covid result and indicating compliance with the public health measures they were taking. Proof of acceptance was necessary for a boarding pass. Wouldn’t you know, there was a glitch in the computer program and the form kept bouncing back. I called a friend in Beirut to see if I might be expressing my Lebanese phone number incorrectly but in spite of various iterations, the form wasn’t moving forward. Computer glitches do to me what stalled traffic does to some others – I just go berserk. As I was frothing at the mouth, my husband told me we’d sort it out at the airport so off we went.

At the airport there were unfortunate souls who had gotten the wrong Covid test and were not allowed to board. I was given another Lebanese government website to which I could submit my negative PCR test so I was allowed to proceed to the airline counter. I felt sorry for the airline personnel who were trying to enforce the restrictions of overseas governments.

When I finally landed in Beirut I was given another PCR test at the airport and a few days later was told it was negative. I looked up my flight on-line and saw that all of us on that flight were equally fortunate. Only one or two passengers on flights from Turkey were found positive at the airport that day. Ten days later I got my final Covid test as required by the government and I was finally allowed out of quarantine and given the same freedoms as everyone else here, which were nearly none. I had arrived in the middle of a strict lockdown. A friend arranged grocery deliveries for me as that was the only way to get food. I had arrived in Beirut six months after the port blast, a disaster I had missed by a week. As the taxi took me from my quarantine hotel to the neighborhood where I was going to stay, I passed familiar streets, now desolate of people and commerce. I found myself saying “good-bye” rather than “hello”. The Beirut I love is gone and I doubt it will return.